Most women I know feel that the split of managing household tasks is. . . unbalanced between their partners and themselves. A recent article in The Washington Post backs up that feeling with these statistics: “Employed women partnered with employed men carry 65 percent of the family’s child-care responsibilities. . . Women with babies enjoy half as much leisure time on weekends as their husbands. Working mothers with preschool-age children are 2 1/2 times as likely to perform middle-of-the-night care as their husbands. And in hours not so easily tallied, mothers remain almost solely in charge of the endless managerial care that comes with raising children: securing babysitters, filling out school forms, sorting through hand-me-downs.”

Most women I know feel that the split of managing household tasks is. . . unbalanced between their partners and themselves. A recent article in The Washington Post backs up that feeling with these statistics: “Employed women partnered with employed men carry 65 percent of the family’s child-care responsibilities. . . Women with babies enjoy half as much leisure time on weekends as their husbands. Working mothers with preschool-age children are 2 1/2 times as likely to perform middle-of-the-night care as their husbands. And in hours not so easily tallied, mothers remain almost solely in charge of the endless managerial care that comes with raising children: securing babysitters, filling out school forms, sorting through hand-me-downs.”

I don’t know about you, but those numbers feel eerily accurate. The mental load of motherhood is weighing a lot of us down.

It is okay to want credit.

My nine-month-old has had a rough month. We started with a bout of RSV and finished up with a weekend of Roseola. Oh, and separation anxiety settled in. My husband has affectionately been calling my baby my barnacle for the last few weeks. The extra affection is incredibly sweet, but also exhausting. One day when my baby was particularly barnacle-y and only napped on me, I reiterated by exhaustion to my husband after he came home. I felt appreciated when he told me that staying home with a sick baby was much harder than his day at work. I felt energized when he said this. He was right. More importantly, I needed him to notice.

One of the hardest parts about all of the scheduling/Amazon-ordering is how invisible it is. It often goes completely unnoticed by others in the household. I encourage clients to tell their partners about the hidden work saying, “I need you to notice.” Once partners do, often they begin noticing all the time when there is toilet paper stocked and a packed diaper bag before swim class. Although this does not negate the need to split the work, knowing that someone is appreciative for all that you do brings awareness to how much work there is to be done and how hard you are working.

We need them to anticipate.

From conversations in my personal and professional life, I know that many women are conflicted about how to talk to their partners about divvying up household tasks more evenly. Many have reported that they don’t know how to implement a change. Others express confusion, as their husbands help out much more with childcare than, say, their fathers did, however, they constantly struggle with tackling the seamlessly endless amount of “tasks” that rack up outside of childcare.

My working mother has a telling story where, in the haze of having three children under the age of two (I can’t even imagine), she often found herself feeling slightly underwater. My father, who was very hands-on, particularly for their generation, would ask her, “What can I do to help?” and she would reply, “Anticipate!” Sound familiar?

Many women feel as my mom did. We feel we are the captain of the ship, directing and asking our partners for help when they should be just as capable of proactively managing the mental load as we are.

Now, this is an incredibly complex topic that touches on gender norms, societal pressure and personal dynamics which I can’t begin to address in one article. However, I do want to focus on one big piece of the puzzle: communication. Sometimes, finding ways to communicate the need for help is hard. As a therapist, I know that communicating our needs effectively can take some work. Often, we keep these feelings pent up until we can’t take it anymore.

Show your math.

I often tell clients, “You need to show your math.” Meaning, while the goal is for your partner to issue-spot independently, we might have to help them get there and build that skill. How? The first step is communicating in a way that allows your partner to understand what you and your family need and how to support you.

As a starting point, here are some useful ways to begin addressing the conversation:

Never start a conversation angry.

I see a very common pattern among my clients and friends: when we try to talk to our partners, we are already angry. We often don’t intend to start the conversation this way. However, we start to notice that we are taking on more at home and while we might not voice this feeling, we are taking mental notes. Sometimes, we might make an off-handed comment but don’t address the issue directly and our partners do not pick up on a cue.

Then something happens and we are mad. Really mad – all our feelings on the topic just spill out all at once. We didn’t intend for this to happen but think about it from our partners’ perspective. When we start a conversation angry, we change our tone, we raise our voice, and we tend to speak in all-or-nothing statements. Our partners are likely to feel like their backs are against the wall and they’re either going to say nothing or get extremely defensive.

Try to keep resentment from building up.

When we get to the point where you have a mental list of everything that is bothering us, we’re already angry. Think of anger as a balloon filling with air. If the balloon gets too full, it pops. Find small ways to let the air out little by little. Find ways to have smaller conversations in-the-moment or as soon as you feel initial resentment building.

We each speak. We each listen.

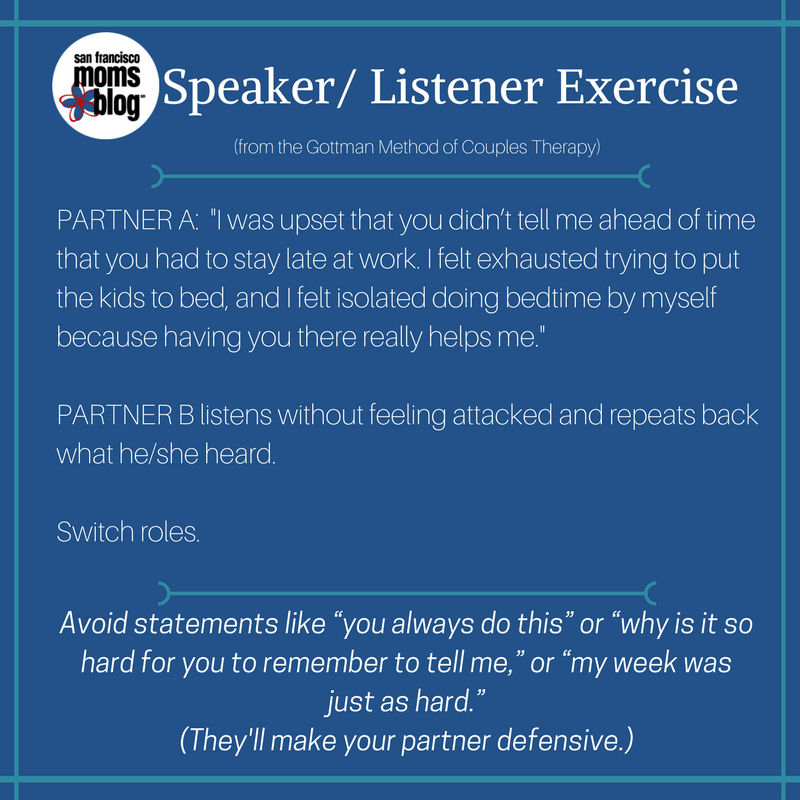

One of the most useful exercises I use in my practice with couples comes from the Gottman Method of Couples Therapy and is called Speaker/Listener. The goal is to listen to each other and try to understand the other’s point of view. In the exercise, each partner states how they feel about a certain topic. In this scenario, one partner states that she felt that she was handling the burden of household work. Using non-blaming statements, that partner expresses how she feels. The other partner listens and can take notes. At the end, her partner shares back how she is feeling. Her partner does not have to (and often doesn’t) agree with her but is just trying to understand her experience.

Then, the couples switch roles. You should try to voice how your partner feels and your partner should do the same. What does it feel like to be heard? The purpose of this exercise is not to pick a winning argument but to try to understand where each other is coming from. I suggest couples use this exercise, however, don’t start with household tasks. Try this informally and then build to the harder conversations.

Play to each other’s strengths.

A few years ago, a hilarious-and-slightly-horrifying trip to Safeway led to my discovery that my husband did not know that supermarkets had a deli counter and a meat counter. Something teachable? Sure. But to be honest, I don’t mind taking on the food shopping. But I hate the garbage. I hate the smell, I hate touching it and I never remember it has to be moved to the curb on Monday night. Therefore, my husband is the designated garbage czar in our house. I could try to do the garbage, but it is so much more unpleasant work for me than, say, folding the laundry. And so we divide and conquer based on what we like (or at least don’t hate the most). I suggest that you sit down with your partner and try to devise a system that works for you both. Perhaps even have a chore “draft” where you each pick one or two things to handle.

Conversations regarding roles at home and divvying up chores can take a while to iron out (pun intended). I highly recommend marriage meetings as a way to fully address your feelings. State what you need clearly and then start a running conversation. Do some work before the meeting and determine what areas you can completely delegate to your spouse? What areas do you want to be involved in? After enough conversations, you’ll determine how to find a better balance that’s acceptable for both partners.